Temple Architecture - The Mosaic Windows

The Mosaic Windows

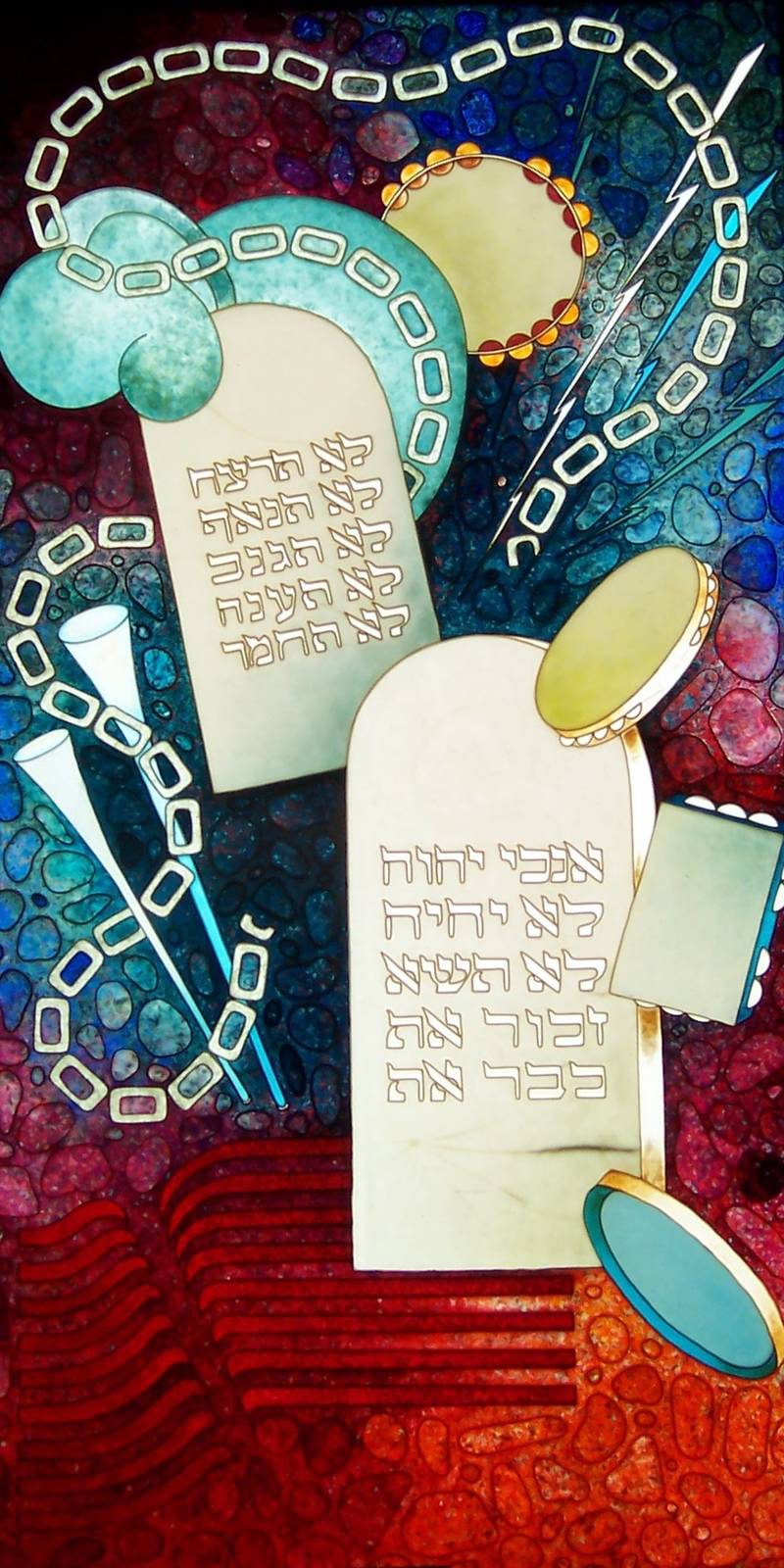

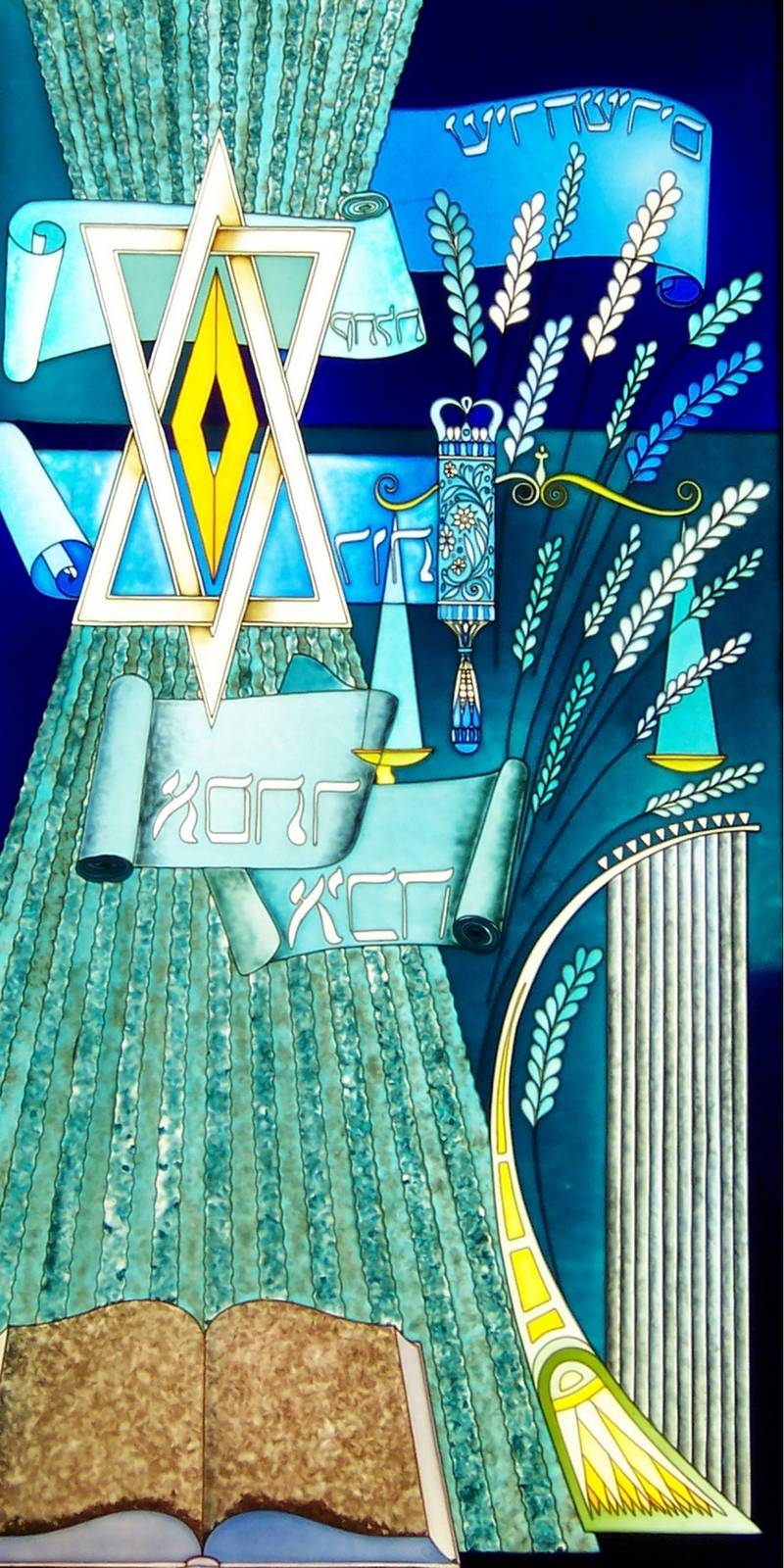

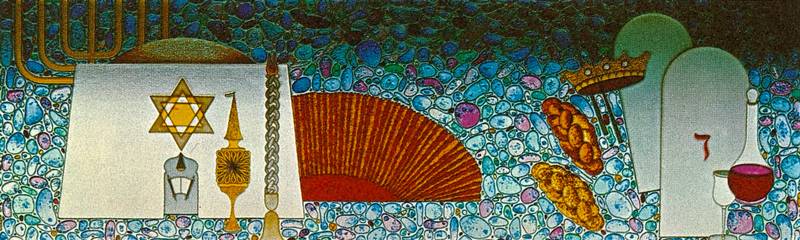

The 8 main panels (representing Creation, Revelations, Worship, and Redemption above and Sukkot/Simchat Torah, Shabbat, High Holy Days, and Passover/Shavuot below), and the 36 (plus 1, installed in the lobby) accent panels are the work of Schenectady-born artist Charles Van Atten.

The Artist

After spending most of his childhood in New England the artist attended Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, now the art school for Tufts University. Following his education Van Atten worked as an advertisement designer and colorist before moving onto a career as an interior designer. Charles moved to Florida in the 1950’s and established “Van Atten - Designers, Colorers, Craftsmen.”

Van Atten described the process of manufacturing his unique, “Mosaic Plasti-Glass” panels in a series of letters to temple leadership:

“About seven years ago (1955) a client showed me a rough idea which consisted of a strip of blotting paper cemented on edge to a piece of sheet of plastic, with fragments of a bottle. After approximately two years of experimental development I devised a system to expedite making luminous panels of any motif or pattern...

Mosaic Plasti-Glass is made from the finest resins and glass fibres, colorants, granulated stained glass and specially constructed third-dimension design cells. These materials are fused chemically into a hard solidified state. The moisture-proof edging of cellular cellulose acetate has unusual impact strength.

Luminous walls and ceilings, windows, doors, murals, dividers, and screens can be created with Mosaic Plasti-Glass to provide an atmosphere of brilliant distinction. An important advantage of Mosaic Plasti-Glass is the fact that the design can be seen in full color with normal light on one side, while the opposite side with less illumination has the quality of stained glass.”

Dedicating the Windows

On May 3, 1964 the sanctuary’s beautiful mosaic windows were dedicated by Bertha and Harry Schaffer and Sally and Henry Schaffer in memory of the brother's parents Abraham and Annie Schaffer during CGOH’s 100th anniversary celebration.

Henry ran a local chain of grocery stores named Empire Market, considered to be the first grocery chain in the state. Henry met Sally when she was a young librarian at Union College. Henry and Sally were major local philanthropists who donated $500,000 toward the construction of a proper library building on the Union campus. Fittingly, it was named the Schaffer Library.

Modern Contemporaries

Van Atten wasn’t alone when it came to developing alternatives to traditional stained glass windows in the mid-20th Century. The First Presbyterian Church in Stamford Connecticut, designed by Wallace K. Harrison (c.1958 and seen below) is known for its unique shape (hence the nickname “the fish church”) and its slanted walls of chipped and faceted structural “dalle de verre” glass (above). The technique was developed by Jean Gaudin in Paris in the 1930s.

Dalle de verre glass is thicker and provides deeper colors than traditional stained glass. In the Stamford church it was used to create abstract depictions of the crucifiction and the resurrection of Christ.

Wallace used dalle de verre glass again in his Hall of Science, one of the few remaining buildings built for the 1964/65 World’s Fair (below).

Another example of modern stained glass design can be seen at Percival Goodman's Temple Beth Emeth on Academy Road in Albany. There, the window artist (Nathaniel Kaz) incorporated window panels of the congregation's former temple on Swan Street into a composition of seven narrow, vertical "lancet" windows that form the backdrop for the ark and bimah. The windows contain motifs representing the seven days of creation in a mural-like fashion.

In Chicago the fittingly named "The Loop Synaogue" of 1960 also employed modern design techniques that utilized traditional stained glass to create a colorful and rich tapestry of "iconographic elements based on the artist's (Abraham Rattner) knowledge of ancient and medieval mystic Judaic conceptions of the origins and structure of the universe, God's relation to it and man's place within it."

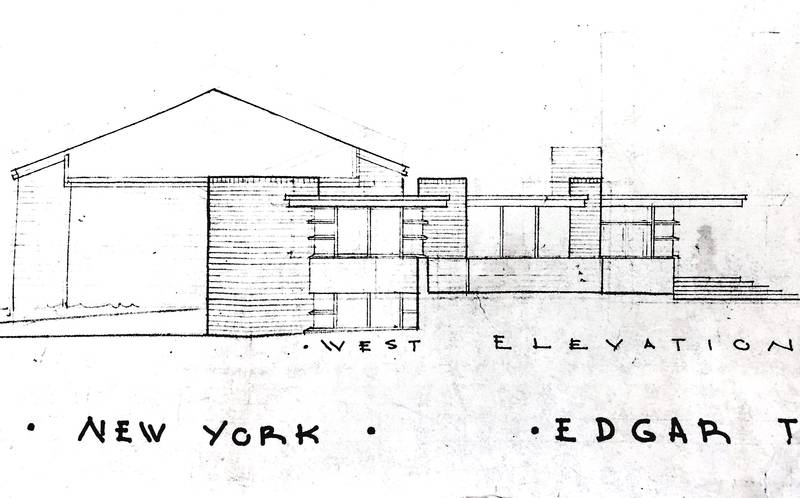

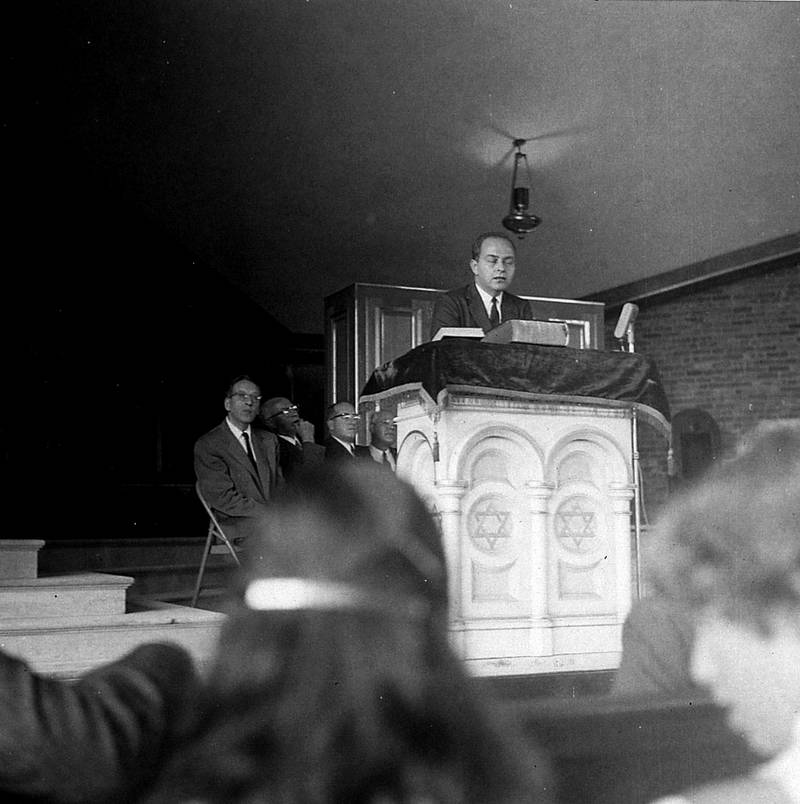

Temple Architecture: The Architect

Looking at it today it might be hard to believe that the temple’s design was influenced by the work of famous architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. In fact, the architect of the temple’s original mid-1950’s form was one of Wright’s earliest and most accomplished apprentices, Edgar Tafel, seen below speaking at the lectern on October 8th, 1956 - the second day of the temple's two day dedication.

Edgar Tafel, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was born in New York City in 1912. After leaving New York as a young man he moved to Wisconsin and became one of the original members of Wright’s “Taliesin Fellowship”. Tafel worked closely with Wright on many of his most famous works, including the iconic “Fallingwater” in Bear Run Pennsylvania. In an article on Fallingwater from 2002 Tafel was quoted as saying “He was a great architect... but he needed people like myself to make his designs work—although you couldn’t tell him that.”

Edgar Tafel, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was born in New York City in 1912. After leaving New York as a young man he moved to Wisconsin and became one of the original members of Wright’s “Taliesin Fellowship”. Tafel worked closely with Wright on many of his most famous works, including the iconic “Fallingwater” in Bear Run Pennsylvania. In an article on Fallingwater from 2002 Tafel was quoted as saying “He was a great architect... but he needed people like myself to make his designs work—although you couldn’t tell him that.”

In 1941, Tafel left Wright’s practice to open his own office and raise a family. Wright did not take the news well and a rift developed between the two. Apparently still feeling the sting of the loss of Tafel’s talents Wright, a year later in 1942 wrote "Somehow I regard the advent of another Tafel in the world as of inferior consequence compared to a Tafel able to carry on a work in the world of loyalty based upon right-minded ideas instead of selfishness."

Despite this, Tafel and Wright continued to maintain a sometimes contentious friendship that lasted until Wright’s death in 1959. Tafel also kept in touch with Wright’s infamous widow Oligvanna; visiting her at Taliesin West and attending her funeral a few years later. Never forgetting the influence the Taliesin Fellowship had on his life Tafel would write multiple books about his time working with Wright and in 1995 produced a documentary that featured the recollections of four of Wright’s apprentices..

Tafel went on to have a successful career designing homes, college campuses (SUNY Geneseo, Fulton-Montgomery Community College in Johnstown, N.Y, and Columbia-Greene Community College in Hudson, N.Y. among them), and religious buildings. His design philosophy rebelled against the predominant “glass box” style of post WWII architecture through the use of brick facades that incorporated design aspects of his “Prairie School” education under Wright with ornamental motifs of the past (such as Gothic quatrefoils). This can be seen in the design for a church house completed in 1960 for the First Presbyterian Church at Fifth Avenue and 12th Street in Greenwich Village. Tafel designed the building to compliment and blend in with the adjacent c.1846 Gothic Revival church.

Tafel lived to be 98 and in 2011 was the last member of the original Taliesin Fellows to die. Tafel was married twice, ending in divorce and the death of his second wife in 1951. Despite his leaving Taliesin to start a family in 1941 he had no children.

Though now unrecognizable following decades of additions and alterations to the temple there were what seemed to be homages to Wright’s work, Fallingwater in particular, in the original design for the entrances to the office, lobby, and kitchen areas - as seen in the images below of Fallingwater and a c.1954 concept rendering of the west elevation of the temple. We will explore the design of the temple and how it has changed over time in upcoming posts.